A Bunch of Nonsense?

This post was written in preparation for our May 2017 concert, Music Speaks

In our 2017 spring concert,

Manitou Winds explores the meandering, mystical path connecting music and words.

We’ve been discussing for the past few weeks how music can enliven poetry and prose — bringing out hidden meanings from the words, engaging the listener beyond what the naked words ever could. But, when the words are basically nonsense, can the reverse occur? Can a composer use words to play with music rather than using music to play with words?

I happened upon Two Songs for Tenor and Wind Quintet and the music of David Jones (b. 1990) while Manitou Winds was still in rehearsal for our debut appearance in 2015. My chance encounter was  thanks to the modern wonders of internet searching. I was brainstorming for ideas and asked the ether of cyberspace for music written for vocalist and wind quintet. Thanks to the internet, discovering undiscovered and unpublished student composers is easier than ever.

thanks to the modern wonders of internet searching. I was brainstorming for ideas and asked the ether of cyberspace for music written for vocalist and wind quintet. Thanks to the internet, discovering undiscovered and unpublished student composers is easier than ever.

David was about to graduate with his Bachelor of Musical Arts in Composition from Brigham Young University-Idaho when I first got in touch with him back in 2015. He’s now received his Master of Music Composition and is presently a graduate teaching assistant at BYU in Provo, Utah. Among his influences, he credits Stravinsky, Debussy, Hindemith, and Holst for shaping his motive-driven style. His brilliant settings of these two songs actually began as a light bit of competition.

“I wrote each of these pieces for two separate art song competition recitals put on by the voice faculty at BYU-Idaho,” David recalled. “The assignment for the first was to write something light or humorous since the recital was being held on April Fools’ Day.”

For a light and humorous subject, David consulted the poetry of Lewis Carroll (1832-1898), selecting Jabberwocky for his text. David says it was the “creative vocabulary” of Carroll’s poetry that initially drew him to it. “The light mood in which Carroll presents what could be considered a fairly dark topic appealed to me, so I sought to capture that in the nature of the music,” David says.

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought—

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!One, two! One, two! and through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.“And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!”

He chortled in his joy.‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.— “Jabberwocky”

from Through the Looking-Glass (1871) by Lewis Carrol

First published in 1871 as part of Carroll’s novel Through the Looking-Glass (the sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)), Jabberwocky remains one of the greatest nonsense poems ever written in English. Beneath the surface of the playful  language is a tale of the heroic slaying of a terrifying beast, but somehow it’s the words that stick with folks rather than the gory details.

language is a tale of the heroic slaying of a terrifying beast, but somehow it’s the words that stick with folks rather than the gory details.

“It seems very pretty, but it’s rather hard to understand!… Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas — only I don’t exactly know what they are! However, somebody killed something: that’s clear, at any rate.”

— Alice

from Through the Looking-Glass

David’s setting pairs the modern-day wind quintet (flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon) with a vocalist armed with Carroll’s playful lexicon. What results is a fantasy tale set to music. Using a central theme presented by the vocalist, David manipulates the timbres of the quintet in inventive ways, altering the theme as needed to further portray the story.

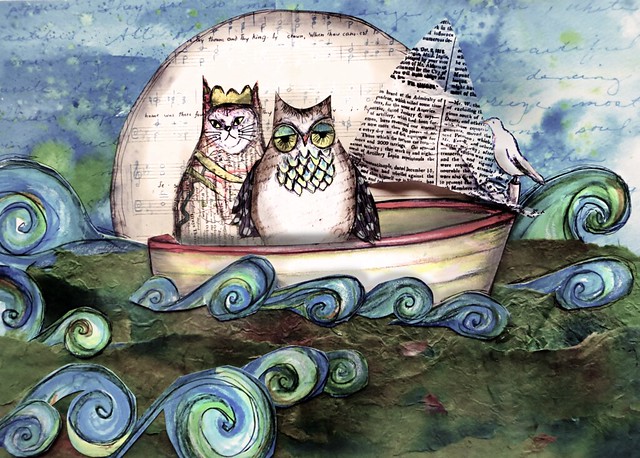

The second song was written under slightly different circumstances: another competition but slightly different rules. All of the composers were required to use the same text: The Owl and the Pussycat by Edward Lear (1812-1888).

The Owl and the Pussy-cat went to sea

In a beautiful pea-green boat,

They took some honey, and plenty of money,

Wrapped up in a five-pound note.

The Owl looked up to the stars above,

And sang to a small guitar,

“O lovely Kitty! O Kitty, my love,

What a beautiful Kitty you are,

You are,

You are!

What a beautiful Kitty you are!”Kitty said to the Owl, “You elegant fowl!

How charmingly sweet you sing!

O let us be married! too long we have tarried:

But what shall we do for a ring?”

They sailed away, for a year and a day,

To the land where the Bong-Tree grows

And there in a wood a Piggy-wig stood

With a ring at the end of his nose,

His nose,

His nose,

With a ring at the end of his nose.“Dear Pig, are you willing to sell for one shilling

Your ring?” Said the Piggy, “I will.”

So they took it away, and were married next day

By the Turkey who lives on the hill.

They dined on mince, and slices of quince,

Which they ate with a runcible spoon;

And hand in hand, on the edge of the sand,

They danced by the light of the moon,

The moon,

The moon,

They danced by the light of the moon.— The Owl and the Pussycat (1871)

by Edward Lear

David readily admits he was not terribly fond of the assigned poem initially. Lear’s poem, like Carroll’s, is considered a nonsense poem but — unlike Jabberwocky — the nonsense comes more from the subject of the story and the poet’s whimsical plays on words rather than extensive use of nonsense words.

Students were assigned to use different instruments or sounds to represent various characters from the poem. David uses a central theme to carry the poetry, again, however for the quintet accompaniment he employs even more colorful uses of harmony, dissonance, and instrumentation to mirror events in the poem. In his setting, we hear several quirky harmonies, lop-sided rhythms, and even a few specific animal references (e.g., when the oboist is asked to crow his reed to simulate a pig’s squeal).

We’ve been enjoying rehearsals of these whimsical pieces — delighting in the crunchy harmonies and unexpected twists. For our concert, we’ve enlisted the vocal talents of our special guest, Emily Curtin Culler, soprano. Manitou Winds is delighted to present these two original settings of classic poetry for our Music Speaks concert.