Three Celtic Carols

This post was written in preparation for our December 2015 Winter Songs & Carols concert. For information about our next Winter Songs & Carols program or our other seasonal performances, visit our Performances page.

While putting together arrangements and selections for Manitou Winds'”Winter Songs & Carols”, I sought pieces that would be a departure from what our audience might expect to hear during a season usually filled with Christmas concerts. Part of that departure was accomplished by selecting tunes that have a stronger connection to the celebrations of Advent or Winter Solstice than Christmas. But, I also sought out Christmas tunes that were perhaps less popular or overshadowed.

While researching, I noticed a lack of Celtic representation in literature for winds. Joining my search for overshadowed tunes with my love of Celtic music, I became inspired to create a small suite of carols with Celtic origins written expressly for wind quintet.

Three Celtic Carols

When people think of Celtic music, they most commonly think of Ireland or Scotland. However, the Celts inhabited quite a large area of Europe in ancient times. Roaming the countryside of northern Spain and France, for instance, you can find prehistoric Celtic sites that very closely resemble those found in Ireland and Scotland. Celtic influence in those areas is unmistakable and continues into the modern era. So, while these tunes may be only partly Celtic when examined closely, they are unarguably influenced by the Celts.

Movement I: Jesous Ahatonhia

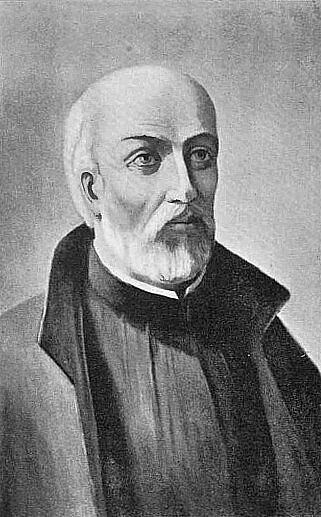

- The lyrics of this carol are believed to have been written by Father Jean de Brébeuf in 1642 while he was working as a missionary in New France,

ministering to the Huron (Wyandot) tribes.

ministering to the Huron (Wyandot) tribes.

While it’s now common to think of missionaries from the days of colonialism as mere invaders, Brébeuf’s earnest and compassionate efforts to learn the language and culture of the Huron people is compelling. Rather than attempting to convert them to Catholicism by forcing them to learn French, he translated French texts into Huron.

Naturally, Brébeuf wrote his carol in Huron, the lyrics transporting the story of the Nativity from Bethlehem to the New World. Rather than a manger in a stable, Christ was born in a lodge of broken bark, swaddled in rabbit’s fur. The three Magi were hunters who brought gifts of fox and beaver pelts rather than frankincense and myrrh.

‘Twas in the moon of winter-time

When all the birds had fled,

That mighty Gitchi Manitou

Sent angel choirs instead;

Before their light the stars grew dim,

And wandering hunters heard the hymn:

“Jesus your King is born, Jesus is born!” — English translation of the first stanza

The carol’s Celtic connection (though admittedly murky) lies in Brébeuf’s birth in the Normandy region of France which had long been a part of the Celtic nation  of Brittany (see map) and had strong Celtic influence even once the two regions were separated politically. The folk tune which he adapted for his lyrics (Une Jeune Pucelle) may have directly originated in Brittany as well, but due to its folk origin this cannot be said for certain.

of Brittany (see map) and had strong Celtic influence even once the two regions were separated politically. The folk tune which he adapted for his lyrics (Une Jeune Pucelle) may have directly originated in Brittany as well, but due to its folk origin this cannot be said for certain.

Tragically, Brébeuf and many of his converts were eventually captured, tortured, and killed by the Iroquois. Musically, I find it difficult to marry peace and hope with danger and violence! So, in my treatment of this carol, I sought to portray for the audience the sense of danger and the unknown Father Brébeuf and his companions must have felt while journeying across the Atlantic to minister to the Huron people.

Movement II: Carúl Inis Córthaidh

- The tune and lyrics for this carol undoubtedly originated in Ireland but a precise date for its origin cannot be pinpointed. Both the lyrics and the tune may be as old as 12th century or as new as 18th century. Whether the lyrics were originally written in Irish Gaelic or English is also debated since the only Irish version that can be found contains a rhyming scheme more indicative of 19th century Irish than medieval Irish poetry.

We do know the tune was transcribed by William Grattan Flood, organist and musical director at St. Aidan’s Cathedral in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, directly from from a local Irish singer. Flood submitted the carol for publication in the Oxford Book of Carols in 1928. Its publication in that volume has thankfully led to the carol’s preservation and eventual spread around the globe through many other hymnals that followed.

I have always found the tune intriguing, musically, because of its modal inflections (depending  on its treatment, it hints at Mixolydian mode). However it holds special meaning to me since it’s the only traditional Christmas carol that is 100% Irish (both the tune and the lyrics having originated in Ireland).

on its treatment, it hints at Mixolydian mode). However it holds special meaning to me since it’s the only traditional Christmas carol that is 100% Irish (both the tune and the lyrics having originated in Ireland).

For my treatment of this carol, I began by depicting a blustery landscape on the southeastern coast of Ireland — lots of fluttering in the flute and clarinet! As the waves crash upon the coastline (horn and bassoon) and we drift farther inland, we hear the intoning of a cathedral organ beckoning us to come out of the driving wind. Here, a single chorister (oboe) is singing the carol tune and is eventually joined by the rest of the choir. Though the movement begins as boisterously as the first movement, a much more contemplative mood is revealed. As the lyrics suggest, the tune also beckons us to ponder the mystery of the Nativity.

Movement III: Moita Festa

- This tune originates from northwestern Spain’s Galicia region. Galicia was settled by the Celts in ancient times and their influence on the region’s folk

music is quite evident even though the Celtic language in the region has all but died out.

music is quite evident even though the Celtic language in the region has all but died out.

The carol, which has no lyrics traditionally, was composed in 1829 by Joseph Pacheco, music director at the Mondoñedo Cathedral in the province of Lugo (Galicia). The tune name translated from Galician means “many festivals”. Pacheco composed the tune especially for Christmas celebrations — traditionally the only time of year in which the Celtic folk instruments were allowed to join the church orchestra. Traditionally, the tune is presented in a theme and variations form with built-in repeats as the tune goes through each variation.

The Galician musician most responsible for bringing this tune to our modern-day attention is Carlos Núñez. For his 1996 album, The Brotherhood of Stars, he created an arrangement entitled Villancico Para la Navidad de 1829. His recording popularized the tune and has led to many other arrangements and performances by Celtic  musicians outside of Galicia.

musicians outside of Galicia.

I enjoy the mental image of the eager folk musicians who were allowed once a year to add their best musical offerings to worship services. Since those instruments are not part of a wind quintet, I used the tune to depict a young boy awakening on Christmas morning, joyously spreading Christmas tidings through a Galician village as he skips and bounces along his way to the Cathedral for mass. As he makes his merry way, he is joined by more and more villagers who sing along in their unique character to his tune. By the conclusion, we’ve arrived at the center of the village as the great doors of the Cathedral are about to open onto a joyous cacophony of voices and livestock.

Aside from their Celtic roots, what unites these three tunes is that each served as a musical bridge to overcome some sort of divide — whether the differences were linguistic, geographic, or simply cultural traditions. In their own time and in their own way, each of these tunes served to unify people during Christmas.

UPDATE: You can now hear the entire suite of carols on our debut album: First Flight! Visit the Manitou Winds Web Store to order your copy today.

I think you have an incorrect date in this article for the concert. Isn’t the date Dec. 4 – NOT Dec. 5!

Thanks… it was actually an older article from 2015, and I didn’t realize the 2015 concert date was printed in the article. I’ll just take that out!